Plot is an essential dimension of stories, so we need to describe it clearly.

Unfortunately, the word “plot” is used in several, mutually exclusive ways. The resulting confusion interferes with our ability to tell (or write) compelling stories.

For example, the novelist E.M. Forster famously wrote in 1927:

‘The king died and then the queen died’ is a story.

‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot.’*

In short, Forster sees “story” as more simple than “plot.” In itself, this isn’t a problem at all.

Unfortunately, though, the terms “story” and “plot” are used very differently by others. And that creates all kinds of problems!

Confusion in the Ranks

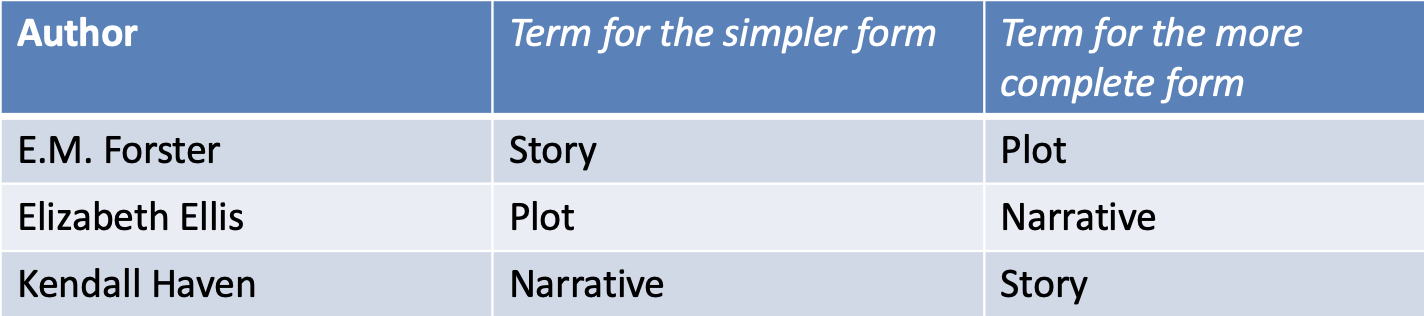

For example, some excellent storytellers have written important books on storytelling, and they make distinctions similar to Forster’s. That is, they each distinguish between a simpler form (Forster’s “story”) and a more complete form (Forster’s “plot”).

So far, so good. But, confusingly, each author uses those terms in different ways:

If this were the only example of story terminology run amok, it wouldn’t matter. But, sadly, this confusing imprecision is widespread—especially among those who set out to explain how to tell (or write) stories.

So what can we do?

One theoretical possibility for avoiding this confusion is to somehow “legislate” the definitions—and try to make people use each term in an “approved” way.

But that barn door has been left open much too long! Getting those horses lined up and properly contained is almost certainly hopeless—especially because the terms “story,” “plot,” and “narrative” are in such wide use in ordinary conversation (with multiple conversational meanings for each term).

My Proposal

Rather than trying to impose a single usage for each term, I propose that we let the words “story,” “plot,” and “narrative” continue to run wild.

Instead, let’s use other terms for the three concepts they represent!

In particular, I suggest that we think of plot as having three levels, that resemble three floors of a building:

The first level (Forster’s “story”) refers to what happens over time: what comes first in the story events, what comes second, etc. I propose we simply call this level “Chronology.”

The second level (Forster’s “plot”) refers to what caused each event. Let’s call that “Causality.”

Finally, we need a third level (which Forster doesn’t mention). In this level, we choose the order in which to describe (present) the story’s events.

A story’s events, of course, need not be told in chronological order. After all, just about every murder mystery story is told (at least partially) out of chronological order. That is, the full series of events of the murder itself (which usually happens somewhere during the first third of the story) is typically revealed near the story’s end.

What should we call This Third Level?

But what name can we use for the third level? That’s not so obvious.

So let’s think a bit more about the function of this level. The author knows, of course, what happened when—and why. But the author also decides in what order to describe those events.

The Tour Guide Analogy

We might compare this third level, then, to the work of a tour guide—like a guide who walks tourists through a series of historic churches in Rome.

We can suppose, then, that the tour starts in a particular square in Rome, where there might be, say, three churches of different ages and different types of architecture. The tour will also visit other churches in other squares.

In that case, the tour guide might choose to take his group of customers to the churches in the order they were built. That sounds reasonable, of course.

But what if the distance between the oldest and second oldest church is so far, that a strict historical order might exhaust the customers? In that case, the tour guide may choose to show the churches in some other order besides historical order.

In short, part of the tour guide’s job is to decide when to see each church—and not necessarily in strict chronological order.

So, we might call this level of plot the “tour-guide level.”

Problem Solved!

Now, at last, we have the option of using three clear terms for the three main layers of plot!

With some of the “plot confusion” resolved, we can—as a discipline—clearly label and discuss these layers of plot, without unnecessary confusion.

In fact, we can create a simple diagram to make it even clearer:

What Do You Think?

So now we have it: three clearly defined levels, each with its own, understandable label. Now we can begin to really talk about plot!

————————————————————————————-

Books referred to:

E.M. Forster: Aspects of the Novel, Kindle Edition, p. 85. Electronic editions published 2002, 2010 by RosettaBooks LLC, New York. (first published in 1927).

Elizabeth Ellis: From Plot to Narrative (2012)

Kendall Haven & MaryGay Ducey: Crash Course in Storytelling (2007)